[Here’s a puzzle for you: There are no pink or orange 16th-century garments in the Topkapi collections, but the art of the period is full of them.1

Rumeli sipahi, a cavalryman from the Balkans.

Two aigrettes and a Persian-esque “crown”

No ornaments

Is it just a painters’ convention, a way to break up the endless ranks of people dressed in fashionable red? Maybe. But why did contemporary European visitors fill their own watercolor books with Ottoman Turks in pink and orange?

The black circle under the tray is a sofra. Source: The Bremen album, 1574

Did Ottoman Turks wear orange and pink?

If the answer is yes, did they wear as much orange and pink as they do in art? Which shades would they have worn? The cost of a dye affected how desirable a color was, so how did orange and pink fit into the fashion landscape? And why are there no surviving pink or orange garments in the palace collection?

If the answer is no, why are pink and orange garments so common in art? Does the answer lie in the pigments, or in artistic conventions?

I’ve been chewing on this problem for over a year. In that time, I’ve concluded that the Ottoman Turks did wear pink and orange–a lot of pink and orange. The colors are easily achievable with kermes and madder, the dyes the Ottomans used to produce true reds. In fact, it’s easier to get pinks and oranges than true reds, because it takes less dye and less skill, especially on dye-resistant fibers like cotton. Orange and pink could be budget substitutes for red, popular for daily wear but not exalted enough to be preserved in the palace collections.

But am I right? Or am I yet another SCAdian who’s letting wishful thinking get in the way of scholarship because I really, really want to wear a hot pink kaftan?

This research project is my attempt to gather all the evidence and consider, systematically, whether the 16th-century Ottoman Turks wore pink and orange. I hope to emerge with a spectrum of glorious new colors to add to our sadly constricted Ottoman palette. Or, alternatively, with a case study in how not to let imagination run away with your scholarship.

Outline

- Extant garments containing pink and orange

- Turkish garments

- Garments from associated cultures

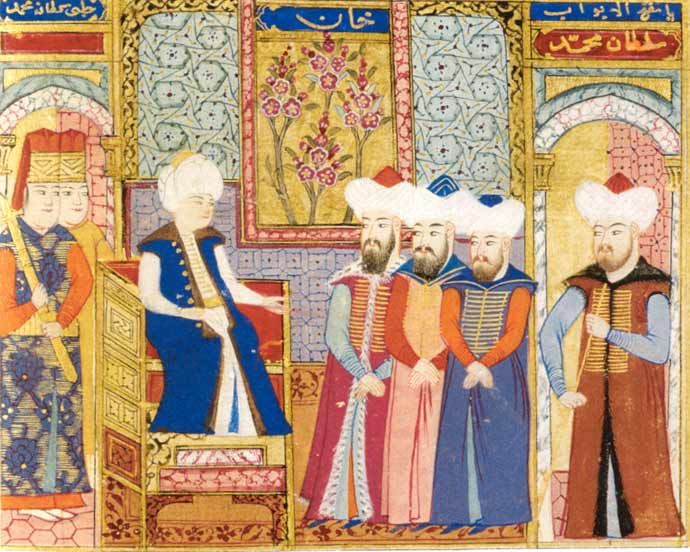

- Artistic evidence

- Turkish art

- European art

- Written evidence

- …from Turkey

- What words did 16th-century Ottoman Turkish have for pink and orange? When were these words introduced?

- Texts that mention (or don’t mention) pink and orange

- Memoirs

- Poetry

- Lists of court gifts

- Estate records

- Turkish color associations. What did red, pink, and orange mean?

- …from Europe

- What words did 16th-century Europeans have for pink and orange? When were these words introduced?

- Texts that mention (or don’t mention) pink and orange

- Travelers’ accounts

- …from Turkey

- Scientific evidence

- Dyes that were used to produce red, pink, and orange

- What dyeing processes were used in period?

- What shades could period dyes produce?

- Pigments that were used to produce red, pink, and orange

- Dyes vs. pigments

- The economics of dyes and pigments

- Dyes that were used to produce red, pink, and orange

- I stretch the definition of the 16th century to cover the first quarter of the 17th century because almost all the detailed Ottoman-drawn images of single figures come from this period. The Album of Ahmed I dates to c. 1610, and the three earliest bazaar albums are dated to c. 1618-1625. Taste in color palettes didn’t change notably from 1600 to 1625, so I consider these sources valid, with a small asterisk.